When I joined the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra in 1997, the AFM-EPF benefits multiplier stood at $4.14, and our orchestra’s contribution rate was 7.5%. Our Orchestra Committee chair regaled me with his perspective that our pension was a fantastic benefit, and I agreed with him. Two and a half years later, the multiplier was up to $4.65, and I was comfortable in the knowledge that my retirement was taken care of, with no further action necessary on my part.

When I joined the Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra in 1997, the AFM-EPF benefits multiplier stood at $4.14, and our orchestra’s contribution rate was 7.5%. Our Orchestra Committee chair regaled me with his perspective that our pension was a fantastic benefit, and I agreed with him. Two and a half years later, the multiplier was up to $4.65, and I was comfortable in the knowledge that my retirement was taken care of, with no further action necessary on my part.

We all know the story of what came next—multiplier reductions step-by-step down to $1. Our orchestra committee negotiated several contribution increases (up to its current level of more than 12.5%), first to take advantage of the great benefit, then to make up for that benefit’s diminution. Should I continue to be complacent about my retirement?

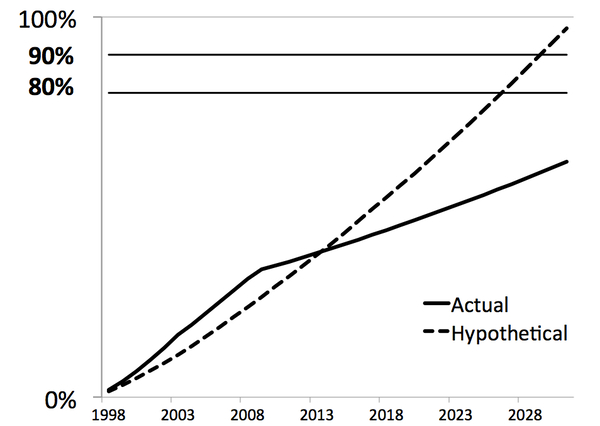

Financial self-help books and online advisors often discuss how much money you need for retirement, and many will frame it in terms of what proportion of your final salary you need to maintain your lifestyle. Ranges of 80-90% are quite commonly cited. One of the advantages of a defined-benefit plan like the AFM-EPF compared to defined-contribution plans such as a 403(b) is the knowledge of how much benefit you will derive in the future. Once you have vested, you can find out (either with a calculator or with the help of the AFM-EPF website) the monthly payment you will receive in retirement based on contributions already made. And it is not complicated to factor in the benefit from anticipated future contributions.

I recently ran a calculation of just such a number, for a hypothetical member of our orchestra, using our current CBA (and conservative estimates of future wage increases beyond its term) to predict future contributions. Self-centeredly, this hypothetical person began work in 1997 and will retire in 2032, but she only makes the minimum annual guarantee, and she never earns seniority. (She is also single.) The twist is that I ran the calculation twice—once based in reality, the other in a halcyon world where the benefit multiplier remained at $4.14, but our contribution rate also remained fixed at 7.5%. Here are the results, showing the cumulative annual pension benefit at retirement as a proportion of final salary:

This chart justifies my complacency in 1997, with a hypothetical retirement income of 90% of final salary. It is also a personal call to action in 2014, with an actual projected retirement income of only 61% of final salary. Currently 73% of ICSOM orchestras participate in the AFM-EPF, and their average contribution rate is about 8.5%. Even with our much higher rate, I’m unlikely to reach the recommended level of retirement income from the AFM-EPF alone. To do so, I would need a contribution rate closer to 25%, according to my calculations, about double the current rate.

At the annual ICSOM conference, the state of the AFM-EPF has been a perennial topic, at least since 2008 when I became a delegate. In view of the diminished multiplier, should orchestras be bargaining additional contributions to the AFM-EPF or shoring up their pensions in other ways, such as an employer match on 403(b) contributions? I think we should be having open discussions about these issues, in the context of balancing the needs of the many against the needs of the few. I’m confident that just this type of discussion was at play recently in Atlanta, where the impact on other orchestras of a possible capitulation to management’s demands on the orchestra complement was surely part of the conversation.

One thing that is not in dispute, however, is that ultimately you are responsible for your own retirement. There are well-publicized personal savings vehicles available to you to supplement whatever pension plan you have at your workplace. Those of you, like me, whose orchestras participate in the AFM-EPF, should be making use of them. And even those who have a private plan that is currently in good shape should not be complacent. As history shows, the justification for that complacency can simply vanish.