Photo credit: Courtesy of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra

It is not unheard of for orchestral musicians to get jobs in their twenties, work really hard for a number of years, and then start to stagnate. Without finding new personal and musical challenges, it can sometimes be difficult to keep growing. You finally win the big job, and . . . then what?

Upon returning to work after our 2012 lockout, the musicians of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra (ISO) took the opportunity to examine the ISO’s institutional culture, and we suggested that the musicians be provided with professional development opportunities in the same way that members of the management are.

This examination led to the creation of a musician-led Professional Development Committee. This group has organized movie presentations, Dalcroze classes, seminars in Alexander Technique, and various other programs over the last few years as a way for us to challenge ourselves and explore various ways to develop our craft together.

This spring saw our most successful event yet when we invited David McGill (an Emeritus member of the Chicago Symphony) to come to Indianapolis to speak about his book, Sound in Motion. In the book, David discusses his application of legendary oboist Marcel Tabuteau’s approaches to musicality and phrasing. The book lists examples and techniques for structuring phrasing, with an eye towards developing musical plans and strengthening the individual musician’s appreciation and application of these concepts to every musical phrase.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra

Before David came to Indianapolis, ISO management agreed to provide copies of the book to any musician interested in participating. Nearly every section of the orchestra joined in, and about thirty of us met in March and April in small discussion groups in members’ homes to discuss how we felt about the ideas we read. Needless to say, lively conversations ensued, and we realized both that we don’t agree on everything and that we love having a forum to talk about it.

We found out right away that we were hungry for this kind of conversation with each other. Groups of musicians spontaneously formed backstage at concerts and rehearsals to discuss note grouping, peaks and valleys within phrases, or whether a violinist would express a chromatic passing tone in the same way that a clarinet player might.

Oboe players who had learned the Tabuteau teaching methods in school found themselves being asked to look at the concertmaster solos from Ein Heldenleben and talk about implied harmonic structure and the resultant melodic shaping one might use in it. Meanwhile, bassoon players familiar with David’s orchestral excerpt CD found themselves discussing bassoon excerpts with violists who had listened to the album and wanted to ask about specific phrasing ideas mentioned.

After we spent a couple of months reading, discussing, and thoroughly digesting the concepts in the book, David arrived in Indianapolis to discuss the book, his reasons for writing it, and some applications of the techniques contained within it.

Forty musicians attended the session, during which five of us played short examples that had been chosen to highlight some of the techniques that we found most interesting or confounding. Selections ranged from oboe solos from Shostakovich and Scheherazade to the violin part for Bach’s B Minor Mass. David’s coaching and application of ideas from the book were inspired and very educational. He started the session by admitting a sense of apprehension at working with fully-formed successful professionals in this way, rather than with students, but we assured him that we had loved reading the book together and were open to any suggestions he might have.

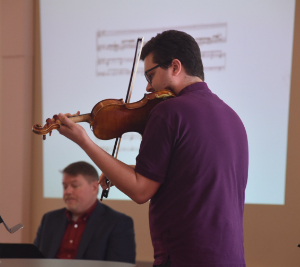

ISO violinist Charles Morey with David McGill

Photo credit: Mike Muszynski

The experience was a resounding success. We exposed ourselves to different viewpoints about phrasing and technique, but we also grew immensely from the shared experience of opening ourselves up to our colleagues. Wind players considered the technical challenges of phrasing and expression in playing a percussion instrument. String players learned where a wind player might want to breathe and, perhaps more importantly, why it might happen in that particular place.

Perhaps more importantly, the community building and personal growth that occurred for us during these months of study and conversation proved to be quite powerful. We loved learning from each other and from David. Many of us found it refreshing to be introduced to a framework for phrasing decisions, and all of us relished feeling more connected to each other in the process of studying, reading, and exploring together.

The idea of management-sponsored and musician-led professional development efforts is a new one to our orchestra. We are finding ways to ask each other what we need in order to keep growing and what we need to keep growing closer and stronger as a group. Some of our efforts have been more successful than others, but our philosophy is that if we reach even a few of our members with any opportunity for lifetime learning, then we are doing our jobs. With the Sound in Motion project, we may have hit our stride in our quest to grow together both musically and communally.

Note: The Authors are members of the Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra.