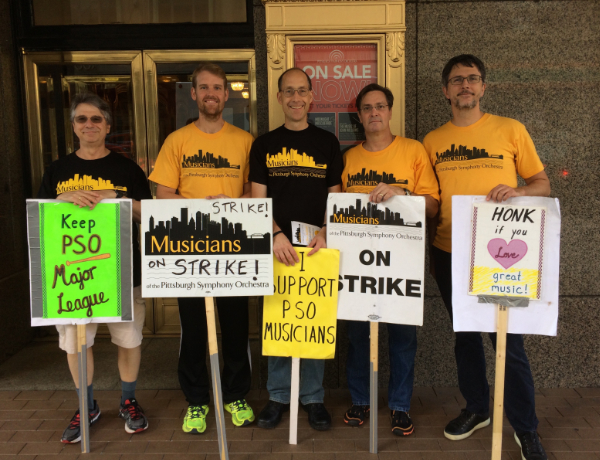

Photo credit: Barry LaPoint

When you’re walking the picket line, and a passerby asks, “Why are you on strike?” you need to have a pat answer, the so-called “elevator speech”. Mine goes something like this: “Our management doesn’t like our pension, which they blame for not having enough money. They want to end it, even though that will cost more money in the short term than staying with the current plan, so they want us to take a 15% pay cut to cover that cost. We believe that will take the PSO out of the top tier of American orchestras, kind of like going from major league to AAA, and we don’t want that to happen.”

Of course, that leaves out a lot of information, some of which is what management would say if they were out carrying a sign, which they aren’t. But a lot of why we are on strike can’t be boiled down in a few seconds. It’s about much more than money.

How do you convey to someone who isn’t a musician what it takes to make yourself into a musician who belongs in one of the world’s best orchestras? How many years, how much discipline and sacrifice, how much money? How can you describe the intensity of a great performance of a great work, your adoration for the way a colleague turns a phrase, or the exhilaration of having one chance to land a lick in real time, and getting it right? How can you describe what it is to be part of an organism, a rare, slow-growing, immensely powerful yet achingly fragile giant, that, for all it costs, gives far better than it gets? How can you put a value on a living art?

You can’t. You can’t tell the man on the street how hard it is to play a concert in, say, Munich one night, and another concert in, say, Frankfurt the next night, knowing that every concert is crucial, that every concert carries the reputation and stature of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, even if you’re tired, even if you’re sick.

Which is why you can’t describe the sense of betrayal you feel when you are blindsided by an initial management proposal that includes a 25% cut, a loss of 10 musicians from the complement, and the ending of the pension—all of which management attempts to justify with projections that suggest the board has no interest in maintaining a world-class orchestra. Or when your CEO says, for the record, that it won’t matter if PSO musicians leave, because “equally talented performers will be happy to fill their spots.” Or when management publishes an “informational” piece that states that a PSO musician only works 20 hours a week and takes three months of sick leave every year.

PSO Oboist Cynthia Koledo DeAlmeida walks the picket line in October

Photo credit: Peter de Boor

You’d like to be able to tell the passerby that you’re not an employee, you’re not a supplier of a product to a corporation, you are the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Your skill as a musician is only a surface layer; it may be obvious that a musician can play difficult music beautifully, but the experience and instinct it takes to lock in with 97 other musicians is harder to appreciate, and is actually much harder to accomplish. Which is why a musician can be a very talented, great player but still not right for a position, and why it can take several auditions, hundreds of applicants, sometimes years, to find the right player for a position in an orchestra like the PSO, which is why it actually really matters if a musician leaves. That’s a pretty fine distinction, though.

So you cut to the chase. You explain that your employer wants to pay for cutting your benefits by slashing your salary and the passerby says, “Yeah, man, that’s messed up. Everybody loves the Pittsburgh Symphony, though, stay strong.”

And it’s true, mostly. You do find the occasional person who wonders how you can be on strike since playing music isn’t even a real job, but the vast majority of Pittsburghers value us. There are those who passionately love what we do, who buy tickets, who donate to the annual fund drive, who listen to our recordings, but there are also the others who think of us kind of like the rain forest. Maybe they’ll never go to the rain forest, but they know that it’s important and they don’t want it cut down. They understand that we’re kind of like the Steelers except for classical music, which is an odd comparison but intuitive to the man on the street. We’ve got six super bowl rings, why shouldn’t we have a great symphony?

The above was, obviously, written while we were on strike, which we no longer are.

After a strike lasting one day less than eight weeks, the Musicians of the Pittsburgh Symphony ratified a new contract. The term of the agreement is five years. The first year imposes a salary cut of 7.5%, followed by two years of freeze, then a 2% and a 6% increase. Three open positions will remain unfilled for the life of the contract, and the defined-benefit pension will be frozen and remaining participants converted to defined-contribution beginning in the fourth year of the contract, with age-graduated supplemental employer contributions. While there is no way to characterize this contract other than as concessionary, it is less so than we would have gotten without a strike, or without our evident willingness to endure a protracted work stoppage rather than agree to a simple downsizing of the orchestra.

Negotiations for this contract began in February, 2016, when management stated that it had no proposal and wanted the parties to negotiate with a mediator but without attorneys (a non-starter for the musicians). Management canceled further meetings until July, when they stunned the musicians’ negotiating committee with the initial -25% proposal. The enormity of the demand, the utter disregard for the drastic artistic consequences of such a cut, and the sudden bearish swing in financial assumptions management attempted to use as justification for their demands, created an immediate, yawning credibility gap. In fact, a cost analysis showed that management’s initial proposal would have yielded a huge budget surplus. One can see how that would look good on paper to a businessman; slash costs, run a surplus, great success. Except, of course, for the part about destroying the organization’s entire reason for existence, and with it the whole reason for the community to support it and the world to pay attention to it.

The board/management storyline has been that years of mismanagement (oddly enough, the very years when the musicians’ concessions of a 9.7% salary cut and the closing of the defined benefit pension to new participants was supposed to be stabilizing the organization) and bad luck have left the PSO on the rocks: overextended on credit, overdrawing on the endowment, and unable to close the gap on pension costs and budget deficits. None of which is particularly shocking to the musicians—we’ve heard this at every negotiation. However, management’s proposals relied not so much on current finances, but on a five-year forecast that contained unrealistically pessimistic projections for both expenses and revenue. Yet our efforts to point that out were met with an almost complete refusal to move the needle. Management viewed its five-year forecast not as a projection, but as incontrovertible fact.

Members of the PSO with guests from the Philadelphia Orchestra, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Cleveland Orchestra, the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, and the National Symphony Orchestra at the Brass Spectacular in October

Photo credit: Courtesy of the Musicians of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

The situation was all the more frustrating, and management’s insistence—that PSO musicians who might be unhappy with more modest wages could be easily replaced—was all the more galling, because the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra has, by all accounts, been playing brilliantly. European tours have been well sold and reviewed, critical response to CD releases (two Grammy nominations in one year) has been rapturous, and ticket sales at home have improved. This would seem to be an excellent time to convey the value of a hometown dream team and advocate its support in response to a problem rather than arguing against that value and tearing it down. But such differences in attitude and value are the stuff of labor disputes.

As the strike dragged on, PSO musicians presented numerous free concerts throughout the community that were extremely well attended and received. A Brass Spectacular featuring the PSO brass section and guests from the Philadelphia, Boston, Cleveland, National, and Dallas brass sections filled the 1700-seat East Liberty Presbyterian Church to standing room only. Orchestral programs, just about one per week, produced similar responses, and chamber groups played dozens of concerts in smaller venues. Our social media committee was extremely active and effective in keeping our cause and message on the front burner. Community support was quite strong, with a steady stream of letters to the editor (and the mayor’s office) arguing for us. Our yard signs were (and remain) everywhere, and our subscribers and donors told us that they were appalled at the way this situation was handled and wanted a speedy, fair resolution before any more of the season was lost.

For most of the strike, chances of that seemed slim. The only modification yielded by a summer of bargaining was a reduction in management’s pay cut demand from 25% to 15%—which management declared was “a huge concession” of its own. After two weeks of federal mediation produced absolutely no change in management’s position, a strike was called on September 30. Seven weeks of the strike were spent with the musicians proposing major concessions in an effort to reach agreement, but with management clinging tenaciously to its demands despite federal mediation and the introduction of an independent financial analyst. They stated that they intended for the PSO and its “new business model” to serve as an example to the nation of how to run an orchestra. Which, evidently, would be a brilliant success if it weren’t for those damned musicians.

Finally, with the holiday pops dates approaching and the tax window for charitable giving closing, the musicians’ bargaining team presented a proposal which included significant enough concessions that any reasonable observer would conclude that the musicians were clearly willing to help bail the PSO out of current troubles, and also included enough provisions for recovery that the musicians could discern some light at the end of the tunnel. After a week of further negotiation, it was this proposal, in essence, that PSO management agreed to.

With the contract only just ratified, it is perhaps a bit early for a denouement, but here goes. Over the course of the strike we learned that we have tremendous community support, and we developed important avenues to build and focus that support going forward. We learned a great deal about our board and management, and what sort of involvement and communication we will need to prevent similar episodes in the future. We experienced the generosity and solidarity of orchestral musicians everywhere, and the hospitality of numerous orchestras who hired us as substitutes. We gained tremendous respect for our colleagues, particularly for those on our orchestra committee, as well as many others who emerged as effective organizers and tireless workers, and for all who walked the picket line with smiles and words of encouragement. We gained confidence in our strength and unity as a bargaining unit, and in our stature as an orchestra. We preserved our identity as a world-class orchestra, and demonstrated our fierce determination to protect it.

PSO musicians (left to right) Michael Lipman, Charlie Powers, Zachary Smith, and Dennis O’Boyle with the Editor (center)

Photo credit: Richard Powers

Yes, we lost some money. It is too early to say what effect this will have on the orchestra because the actual number is less important than the attitude and value it represents, and attitudes and values may change. We have lost players already, and we stand to lose more, but those players were more discouraged by the prevailing attitude that they were not valued here than they were drawn by economic opportunity elsewhere. Most importantly, we have been separated from any illusion we might have had that the PSO was somehow above the sort of corporate autoimmune attacks on artistic quality that visited Minnesota and Detroit, among others. If those on the board and in our community who truly understand what an exceptional, rare, precious thing the PSO is, who appreciate the decades of work and sacrifice it took to create it, and who shudder to think how close we just came to losing it forever, have awakened with us, there is hope.

Note: The Author is a member of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

[…] Fort Worth and Pittsburgh are no longer on strike; see here and […]