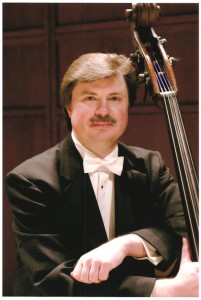

Photo credit: Michael Zirkle

As Bill Bryson noted in his book In a Sunburned Country, life cannot offer many places finer to stand than Circular Quay in Sydney. The glistening panorama of Sydney Harbour and the stunning Harbour Bridge is anchored by one of the most recognizable and iconic buildings ever imagined, the Sydney Opera House. The Opera House was designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, whose dream faced constant criticism, delays, and political attacks that would lead him to resign his post in 1966, never to return to Australia, and never to see his greatest creation. At the opening of the Opera House in 1973, a ceremony that featured an appearance by Queen Elizabeth II, there wasn’t even a mention of Utzon’s name.

That seems a terrible way to treat an artist.

In September of 2020, amid the COVID pandemic that suspended performances everywhere, sixteen members of the Opera Australia Orchestra received notice that the company to which they had dedicated their lives now considered them redundant, and they would be unemployed in less than a month.

Among those sixteen musicians is Mark Bruwel, who at the time of his dismissal was serving as President of the Symphony Orchestra Musicians Association (SOMA). To put that in context for North American musicians, it was as if the Chairperson of ICSOM had been fired unceremoniously and without warning by his or her home orchestra. I felt the shock from the other side of the planet.

Mark, oboist (and cor anglais) for the Opera Australia Orchestra since 1988, told Limelight Magazine that the sudden dismissals brought a “combination of shock, disbelief, fear and a complete sense of betrayal, that the people you entrust guardianship of our art form . . . had just dropped a hand grenade in the middle of the orchestra.”

Paul Davies, the Director of Musicians for the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance (MEAA), released a statement that said, “The result of all this will be that Opera Australia will be diminished in size, [in] its capacity to deliver quality productions, and in credibility.” (Note: the MEAA is the labor union representing the musicians of Opera Australia)

While the pandemic has taken a heavy toll on classical music institutions, most have continued to maintain a commitment to their families of artists. In North America, all but a relative handful of orchestras have managed to retain collaborative relationships with their musicians during the COVID crisis. The same has held true in Australia.

In Sydney, the Opera House attracts over ten million visitors annually with an economic impact in the billions. Opera Australia is the nation’s largest performing arts company, with 2019 ticket revenue of A$73 million; and while they claim these dismissals were necessary due to finances, the company held a A$6.3 million surplus in 2019. Even in the midst of the pandemic, the company sold one of its properties for millions of dollars, yet the sixteen musicians were not rehired. The headline in the March 21, 2021, edition of the Sydney Morning Herald stated, “Musicians not returned as Opera Australia pockets $46 million from property sale.”

“These workers have already taken a temporary pay cut to help the company through the crisis caused by COVID-19,” said Davies. “Now, at the worst possible time, their loyalty has been repaid with a brutal round of forced redundancies and they find themselves unemployed in the middle of the worst recession since the Second World War.”

Mark Bruwel grew up in Sydney, and studied at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. He and I once spent a day hiking along the sandstone cliffs that overlook the Pacific in Manly, near Sydney. Mark was able to recount the history of the beaches, with ocean pools and guard bunkers still standing from the war. As an accomplished horticulturalist and garden designer, he educated me on the vegetation surrounding the paths. Recounting his youth in New South Wales, his first encounter with classical music was from his parents’ collection of vinyl records, with Saint-Saëns and Mahler making an early impact. After performing Stravinsky’s Petrushka with the Sydney Youth Orchestra, his eyes were opened to a career in music, a dream realized when he joined the OAO. He became an essential member of one of the most famous arts organizations in the world, one located in the midst of his home city.

Mark rose to be a leader within the orchestra, serving as President of the OAO’s Players’ Committee, working with MEAA, and ultimately becoming President of SOMA.

His career with Opera Australia would end on March 13, 2020, with a performance of Carmen, but he would have no idea of that until an email arrived out of the blue almost six months later informing him of his redundancy.

I’ve been so struck by the use of that word “redundancy.” It’s not a word used often in America to describe a dismissal, and it seems uniquely harsh, especially for an artist. In Australia and Britain it refers to employment, but in America it typically means “superfluous”. If you aspire to be a great opera company, how is it possible that a full-time English Horn position can be redundant? It can’t be, of course, so it would appear that redundancy can only mean that aspirations have been lowered.

This cruel move has resonated amongst the Opera’s patrons, with one particularly esteemed supporter writing in the September 18, 2020, Sydney Morning Herald, “The word ‘redundancy’ must come as a knife to the heart. One of our national treasures is about to become a debased jewel. I am a longstanding patron of Opera Australia, but I am so angered by the unfairness of this action that I will withdraw my financial support for the company unless the decision is reversed.”

The arts in Australia enjoy widespread public and governmental support. A survey conducted by MEAA in 2019 reported that 83% of Australians support maintaining (and even increasing) funding for orchestras. 84% agree that the arts have a positive impact for mental health, education, and community connection. A study from 2020 by the Australian Council found that 98% of Australians engage with the arts in some way, and in 2019, two-thirds of Australians reported attending a live music performance. But it seems incongruous to value the art without also valuing the artists.

“The employees who actually produce the work that the audience comes to see are being treated as (literally) numbers on a page” observed Mark in our recent exchange of letters. “The artists are no longer celebrated and respected within the Company, but more seen as an annoying necessity.”

In the May 2021 issue of Senza Sord, the official publication of SOMA, former SOMA President Tania Hardy-Smith of Orchestra Victoria commented, “I find it deeply distressing that such a solution was enacted, when from so many other accounts, there are examples of ways in which the orchestra and players were considered a treasure to be mined. This is an already-known, but starkly highlighted realization coming out of the pandemic, and one we must keep prosecuting . . . our livelihood is not just a job. And this outcome must spur all of us on to work hard at keeping our orchestras intact and indispensable.”

I remember a great evening in the Southern Hemisphere winter of 2019 when Tania and I attended Opera Australia’s production of Madama Butterfly at the Opera House to hear Mark and his colleagues perform. After, we met Mark and we all went to a restaurant in Circular Quay. It was a wonderful night with three close friends gathering at one of the most beautiful spots in the world. I could never have imagined that in just a year this renowned opera company would take such drastic action against sixteen of the musicians I’d just heard perform so beautifully.

Sydney Braunfeld, principal horn in the OAO, recently wrote in Senza Sord, “Looking around the pit, I could not help but envision empty chairs where sixteen treasured colleagues should have sat.”

As Mark Bruwel’s years of serving other musicians through his union work should tell you, he is not one to take things lying down, or to stand submissively on the sidelines as this bitter redundancy was imposed. With the able assistance of MEAA, Mark took Opera Australia to Federal Circuit Court alleging a breach of the general protections provided by the Fair Work Act, and a settlement has been reached in his case. Unfortunately, the settlement does not include reinstatement.

A few months before the settlement, I asked Mark what conclusion he was seeking, and he told me, “What Opera Australia did was unconscionable. A global crisis was taken advantage of right when so many musicians were at their most vulnerable. Such behavior is not an acceptable part of an enlightened society.”

Throughout the pandemic, most classical music managements—with notable exceptions—have been able to avoid such ugliness. Generally, musicians have remained employed, community ties have been maintained, and plans have been made to return to performing. Musicians, in their eagerness to sustain their careers and preserve their institutions, have been very willing to make substantial contractual sacrifices.

But for years prior to the pandemic, the word “rightsizing” has echoed from some boards and managements, and from other less-than-inspiring voices. Some have long suggested that our salaries are too high, our complements too large, our ambitions unattainable. Musicians, often through their own ingenuity and advocacy, have managed to maintain their livelihoods, and assist their organizations in growth. As we emerge from the pandemic, musicians anticipate that their absolute dedication to their communities and their willingness to sacrifice throughout the COVID-19 crisis will now be rewarded with concerted efforts to return to where we were in March 2020, as the lockdown moved across the world like the shadows from the setting sun.

Not every organization will share the goals of its artists. The orchestra in the pit of Australia’s most famous Opera House will have fewer full-contract players. The musicians of America’s most prominent Opera House, the Metropolitan Opera, face relentless uncertainty.

Writing for OperaWire on April 2, 2021, journalist Polina Lyapustina wrote with stunning astuteness when she observed, “The end of the pandemic, I assume, will be just the beginning of the fight for rights and safety in the opera world.”

To truly emerge from the pandemic with our artistry intact, we must stand together, united across continents. We must strive to be more caring people, more generous artists, more committed advocates. We’ve still a chance to emerge stronger, but our eyes must be open and our souls alert. We cannot afford to assume this is going to be easy. As corporatism creeps up on the terrain of the artist, we must not diminish our dreams. We are musicians, and every note we play is a call for peace and love to a world in pain.

Jørn Utzon lived to be ninety years old…long enough to see his reputation remade, and long enough to be honored and celebrated for his gift of the Sydney Opera House. Perhaps the sixteen members of the Opera Australia Orchestra, so maligned as redundant by the company they served, won’t have to wait as long.

Note: the author is former ICSOM Chair.